Dr. Paul Stoffels, Vice Chairman of the Executive Committee and Chief Scientific Officer, Johnson & Johnson

It has been 40 years since the first cases of what later became known as AIDS were reported— and despite incredible scientific and programmatic strides, the end of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is not yet in sight. But lessons learned from HIV/AIDS are germane as the world responds to other infectious disease threats, including COVID-19.

We asked Dr. Paul Stoffels of Johnson & Johnson about these lessons, the success of PEPFAR and the importance of global health security for preventing future pandemics.

Dr. Stoffels is Vice Chairman of the Executive Committee and Chief Scientific Officer for Johnson & Johnson where he spearheads the research and product pipeline, leading teams that are discovering and developing transformational healthcare solutions. He also steers the company’s global public health strategy to make medicines and technologies available in the world’s most vulnerable communities and resource-poor settings.

I began my career as a doctor working in Africa at the beginning of the HIV epidemic, when we didn’t know much about the disease and could do very little to help patients. Now, 40 years later, modern science has transformed HIV into a chronic, manageable condition for people with access to treatment.

In these four decades, we have not only learned a great deal about treating and preventing HIV, but also about working collaboratively among multiple organizations and stakeholders. This experience has proven invaluable in the current fight against COVID-19.

However, as I’ve seen firsthand, HIV has taken— and continues to take— a terrible toll on individuals, families, and communities, with the burden falling disproportionately on the world’s most vulnerable. This brings another lesson: it’s not enough to develop new tools. We must ensure they are accessible to the people who need them, which requires investing in sound healthcare infrastructure and frontline workers.

In four decades, we have not only learned a great deal about treating and preventing HIV, but also about working collaboratively among multiple organizations and stakeholders.

Our world is more interconnected than ever before, and as the COVID-19 pandemic reaffirmed, infectious diseases anywhere pose a threat everywhere. This is why proactive investment in pandemic preparedness is so critical. The U.S. government’s leadership, through agencies like the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has been critical, as well as that of groups like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness (CEPI).

It’s not a matter of “if” another pandemic will strike— but “when” and “where.” So we must start working now to build on the lessons we’ve learned from COVID-19— and epidemics before it, like HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and Ebola. There are three things in particular that I believe can help us be better prepared:

First, we must continue investing in breakthrough science, health systems— including frontline health workers— and disease surveillance capabilities. These investments have helped enable the development of COVID-19 vaccines and reinforcing health infrastructure worldwide is crucial if we are to end this pandemic and prevent the next one.

Second, we must continue to build on the public-private partnerships that have been forged over the course of the pandemic. No single organization can prevent pandemics, and the advances made in the development and manufacturing of vaccines powerfully demonstrate what is possible when partners join forces with a sense of shared purpose.

And third, we must ensure that the new innovations are equitably accessible for everyone. The world must support global collaborations like the COVAX Facility, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance— all of which are working to drive more equitable global responses to epidemics.

HIV remains one of the most significant challenges in global health, despite tremendous progress over the past 40 years. Achieving a world without HIV will require a preventive vaccine.

COVID-19 is exacerbating many other global health challenges. For example, The Stop TB Partnership estimated that the pandemic set efforts to end TB back by 12 years, while modeling for sub-Saharan Africa suggests that disruptions to deliveries of antiretroviral therapies could lead to significantly more HIV-related deaths over the next year.

But there are actions the global health community can take now to prevent these losses. A recent Global Fund report found that patients in countries that implemented measures to counter the impact of COVID-19 on health service continuity, such as integrating tuberculosis and COVID-19 testing or providing people living with TB or HIV with extended supplies of medicines, fared better than patients in countries that didn’t.

Developing and scaling these kinds of innovative measures that provide new options for how people receive care can do more than protect against COVID-19 disruptions now. They can also help us reimagine how care is delivered and help lay the groundwork for the eventual end of these entrenched epidemics.

If there’s one thing the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us, it is that more investment and attention is needed for global public health, not less. It will be critical for the global community— across all sectors— to build on the lessons learned we’ve learned and continue prioritizing and advancing global health in the post-COVID era.

The PEPFAR DREAMS Partnership — Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored, and Safe — is public-private partnership involving private companies like Johnson & Johnson, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Girl Effect, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare to address key factors that make girls and young women particularly vulnerable to HIV.

PEPFAR launched in 2003 at a critical moment in the global response to HIV/AIDS, and since then has invested more than $85 billion in efforts to end this global epidemic. Its success demonstrates what can be achieved when the U.S. government commits significant resources, works across agencies, and leads the global community with a clear vision and sense of purpose.

The PEPFAR model is also noteworthy in how it convened diverse organizations and focused their unique strengths in the service of a common goal, often through programs that were community-based, tailored for local contexts and that had specific, measurable outcomes.

This model helped lay the groundwork for other global health “moonshots,” like the 2012 London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal to end tuberculosis by 2030. It is critical that we continue to apply this kind of big-picture thinking and ambition to global health challenges, present, and future.

One example of the ongoing innovation in the fight against HIV is the discreet, long-acting dapivirine ring, which was developed by the International Partnership for Microbicides under an exclusive license from Janssen.

Developing a COVID-19 vaccine is a pillar of Johnson & Johnson’s response to this pandemic, and our single-shot COVID-19 vaccine has received Emergency Use Authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Conditional Marketing Authorization from the European Commission and Emergency Use Listing from the World Health Organization (WHO). We’ve also continued making progress with our Ebola vaccine regimen, which was granted Marketing Authorization by the European Commission in July 2020 and Prequalification by the WHO in May 2021.

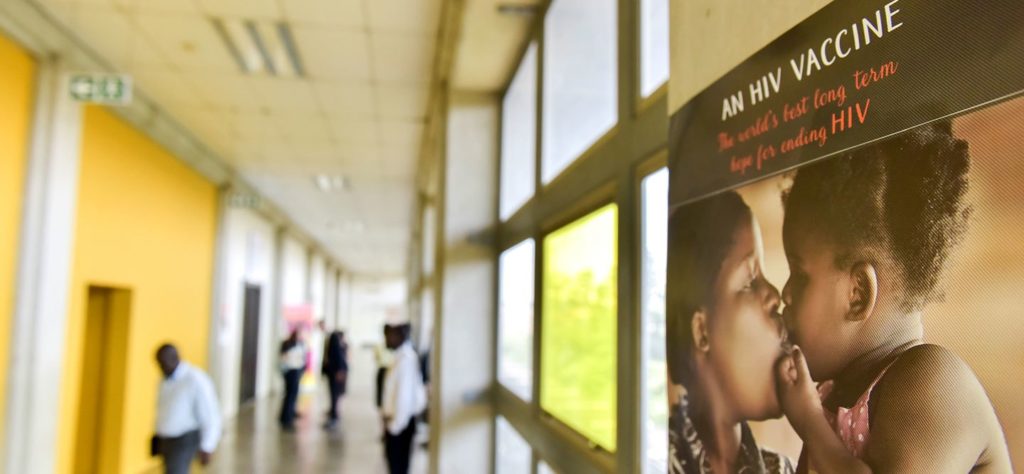

Even as we’ve tackled COVID-19 and Ebola, we’ve not lost sight of that fact that HIV remains one of the most significant challenges in global health, despite tremendous progress over the past 40 years. Achieving a world without HIV will require a preventive vaccine. Finding one has proven challenging due to the virus’ unique ability to evade and attack the immune system and the diverse strains found worldwide.

Together with multiple partners, we’re making significant progress toward addressing this challenge. Our company currently has the only preventive HIV vaccine in late-stage clinical development, and if our investigational regimen is found safe and effective, it could be deployed globally, regardless of the locally prevailing HIV strain. It is now being studied among populations that are uniquely vulnerable to HIV and traditionally underrepresented in research through both the Phase 2b Imbokodo study in sub-Saharan Africa and the Phase 3 Mosaico study in the Americas and Europe.

The vaccine program is just one example of the ongoing innovation in the fight against HIV. Others include the discreet, long-acting dapivirine ring, which was developed by the International Partnership for Microbicides under an exclusive license from Janssen and was recently recommended by the World Health Organization, as well as the world’s first long-acting injectable treatment regimen for HIV, which was developed by Johnson & Johnson and ViiV Healthcare.

These advances, combined with innovative community-based programs, are helping to make further progress against HIV. I am optimistic. I believe that by working together, the global health community will make HIV history.

Photos courtesy of Johnson & Johnson.

Notifications