Watch our exclusive Town Hall with Secretary Bob Gates here →

Having served across eight different Administrations, there is arguably no one more qualified to discuss U.S. foreign policy and America’s role in the world over the last 40 years than former Defense Secretary Bob Gates.

In his new book, Exercise of Power, Secretary Gates reflects on the successes and shortcomings of the U.S. on the global stage, and offers his perspective on a new path forward to confront today’s greatest global challenges.

While the book certainly offers the former defense chief’s insights from being “in the room”, I was most impressed by his thoughtfulness and clarity when it comes to the imperative for strengthening America’s civilian toolkit.

At 464 pages the Secretary definitely covers a lot of ground – so here are my top takeaways on the book from my own USGLC lens:

It’s an impressive message for a former defense secretary of both Republican and Democratic administrations to make the first chapter of his book a clarion call on the failure to invest in our nation’s civilian national security tools.

It’s probably no surprise that I was most captivated by Gates’ view that our nation’s civilian tools remained “underfunded” and understaffed throughout much of the history he covers in the book.

(I also remember how back in 2008 – when the USGLC honored Gates – then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice came by to pay tribute to him as an “active lobbyist for the State Department.”)

Gates also doubles down on his belief that increasing personnel and resources are not enough and reiterates his long-standing message that America’s civilian foreign policy tools must be restructured and recalibrated for the 21st century.

One of the bright spots for the secretary, who served during both the Bush and Obama Administrations, was the success of PEPFAR – both as a highly effective program saving millions of lives and as an arena where the U.S. “received broad recognition and praise.”

Gates also dedicates a chapter to telling the story of Plan Colombia – writing that today’s policymakers have much to learn from the success and “bipartisan support” of Plan Colombia as an “effective application and integration of multiple instruments of noncoercive American power” when the U.S. brought together the entire diplomatic, development and military toolkit.

As one might expect, Gates is certainly not shy to point out the failures he has seen in U.S. foreign policy, from Iraq to Afghanistan to writing a whole chapter on Georgia, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine.

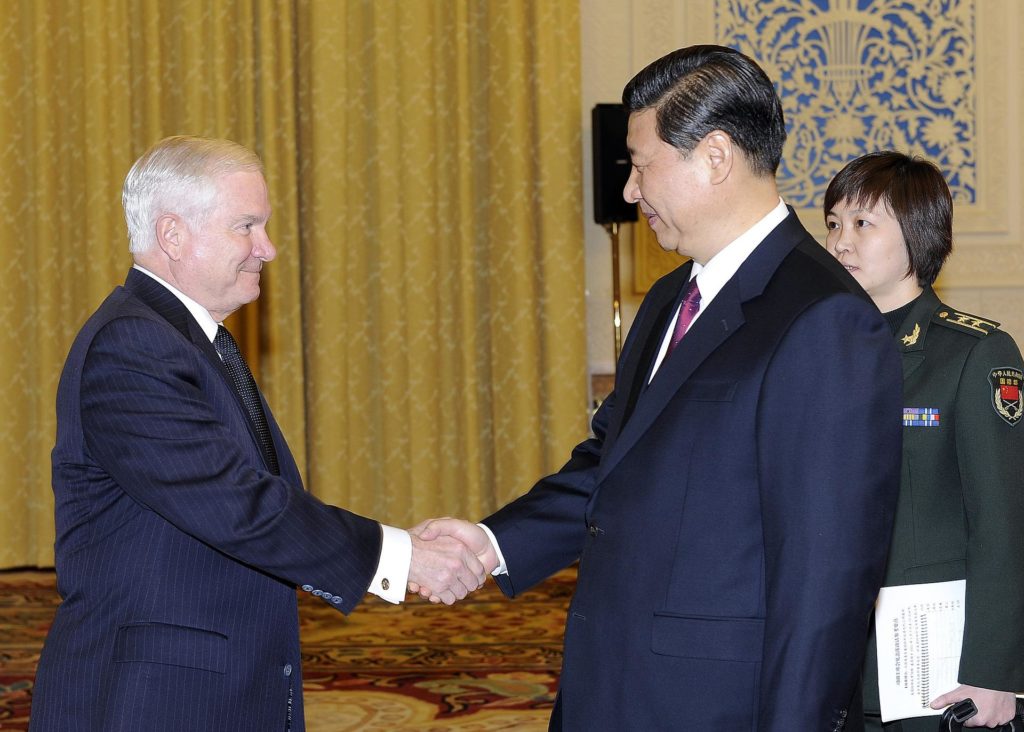

He saved China for the end of the book – but calls the U.S. relationship with China “the most complex, the most daunting, and, potentially, the most dangerous” U.S. foreign policy challenge in the years ahead, and here too highlights their non-military instruments of power.

While the book was written before COVID-19, I’m certain his warnings on Beijing’s long-term strategy still hold true now, given China’s outsized use of humanitarian aid in response to the global pandemic.

A long-term proponent of alliances, Gates writes that this “often undervalued instrument of power… cannot be taken for granted.” And yet he also notes that he too was one who “complained about the failure of allies” to carry their fair share.

One of the other elements of U.S. power that I thought was smart for him to dedicate an entire section to was “The Private Sector” – America’s businesses, NGOs, foundations, and universities. He details a number of these partnerships throughout the book, and also underscores the missed opportunity for the U.S. to do far more on this front.

While Gates certainly champions the outcomes of America’s development and humanitarian assistance, he puts down a marker that the rest of the world often remains “blissfully unaware of our unique contributions” and calls it a “missed strategic communications opportunity.”

The former Secretary ends his book with the critical question that even if we get all the military and nonmilitary tools right, will presidents, Congress, and the American people “recognize that our long-term self-interest demands that we continue to accept the burden of global leadership.”

It’s the question that is at the core of our work at the USGLC – and why I am so proud to continue to tell this story and amplify the support of diverse Americans of all political stripes about why leading globally matters locally, now more than ever.

Notifications